“I can’t think of a single scientific study in the last few decades that has demonstrated that plants or animals are dumber than we think. It’s always the opposite…We keep revealing the fact that all kinds of creatures have a capacity to learn, to have memory, and that we’re at the edge of this wonderful evolution in really understanding the sentience of other beings.”

Robin Wall Kimmerer quoted by James Bridle

To begin the process of imagining an artwork able to ‘cooperatively engage’ with the rich intelligence of the site, I resolved to undertake the observational and listening actions:

Obviously the idea that an artwork could ‘benefit’ the ecological evolution of the site is a relative fiction that must acknowledge the limits of what we can actually know, or indeed assume we might be able to know about worlds we study/work within . In a parallel plane fractal geometry reminds us that there is always more to discover the more you pay attention. Whilst we might expect more order and clarity, in reality ever-closer examination will likely reveal more unexpected variation, nuance and detail. Hence The more accurately you might try to ‘measure’, appraise or describe things, (in so many ways) the more unmeasurable, unappraisable or indescribable they will likely become.

STEP 1: Engaging ‘Spheres’

Classical science tells us that everything can be understood as being part of “spheres”: the so called Geosphere and Biosphere that form the land, water, living things and air – and the infinite complexity of their interactions influence factors such as soil salinity, biodiversity, and landscape formation/composition.

Whilst whilst such conceptual sub divisions are clearly an further divideable abstraction, their value to me lay in reminding me that much that we might easily sense/see/measure/ is limited by our human scale, faculties, ambition, technology and willingness or otherwise to transform the site towards our ends. At best these spheres are therefore interlocking, leaky, and ambiguous – but ideally some facet of each would factor into the forthcoming work.

Geosphere

- “lithosphere” (land) – includes the rocks and soils (which we were already engaging with in a particular way through soil bacteria)

- “hydrosphere” (earth’s liquid water – visibly present on the surface in the still wetland/gulley region of the site, in teh silos and in the air )

- “atmosphere” (the air surrounding (and penetrating) the other spheres)

- (N/A) ” cryosphere” (frozen regions, including both ice and frozen soil);

BIOSPHERE

- (living things, both visible and non visible)

Initial Actions in Regards to the Geo and Biospheres on site:

I resolved to:

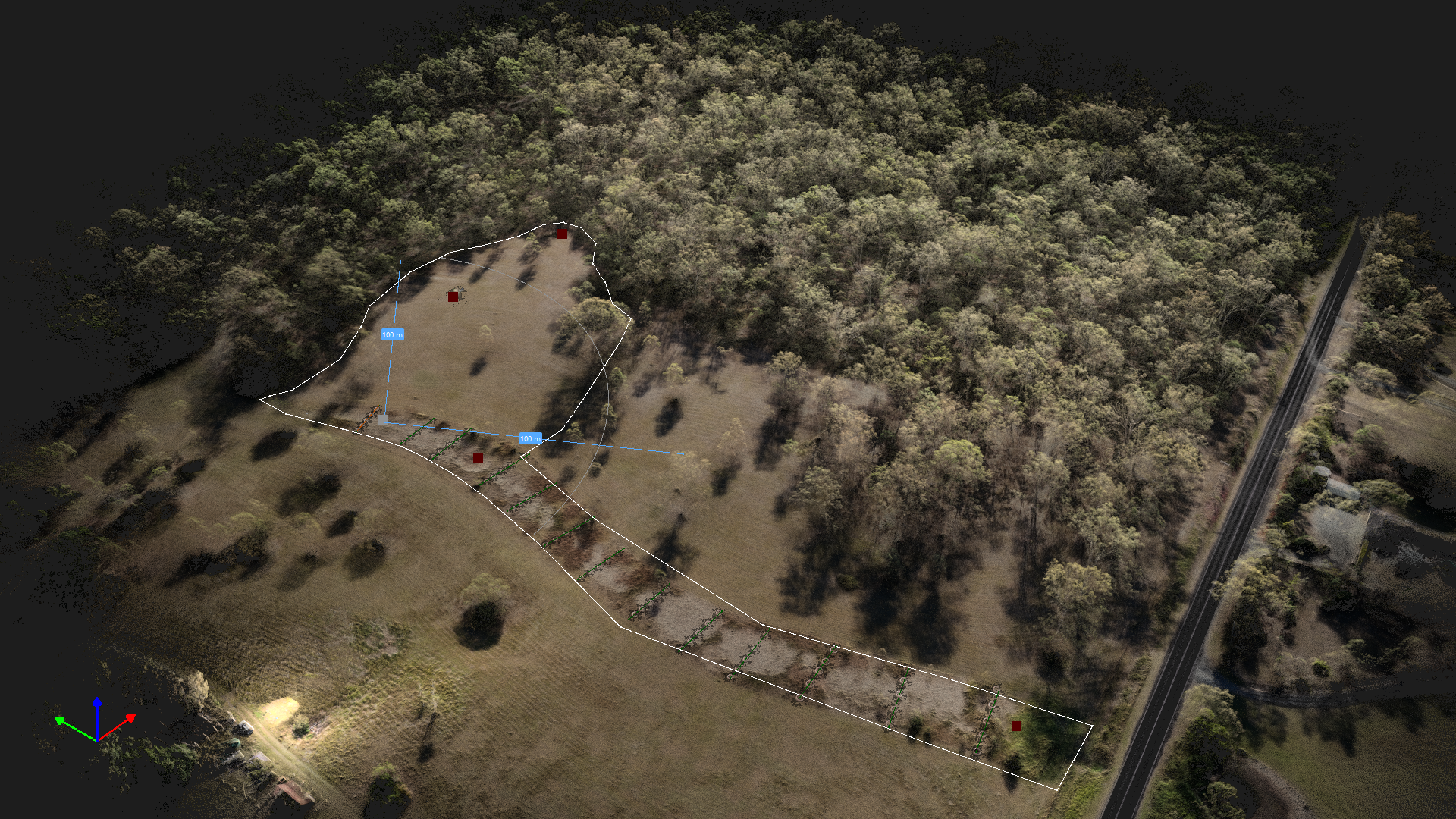

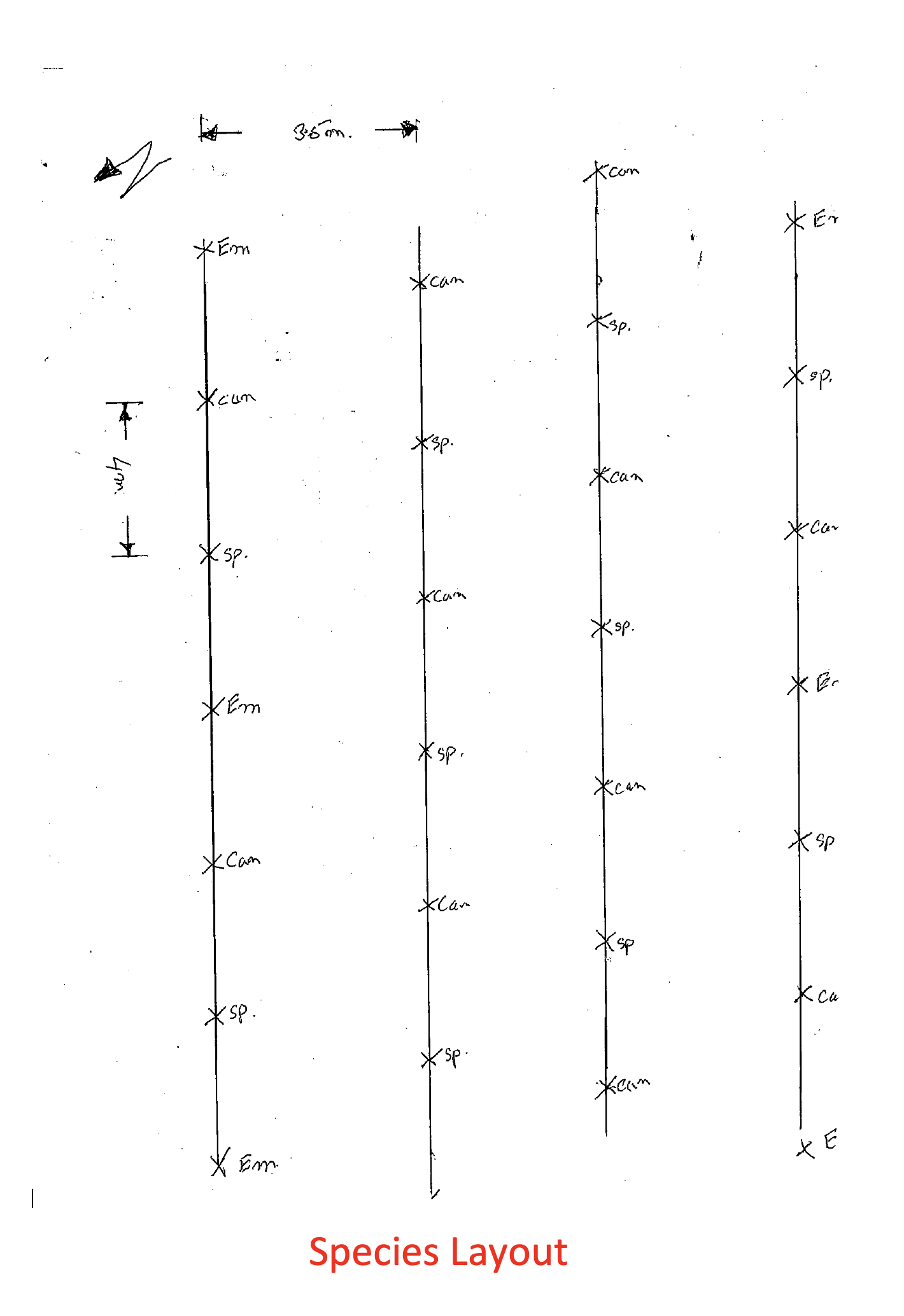

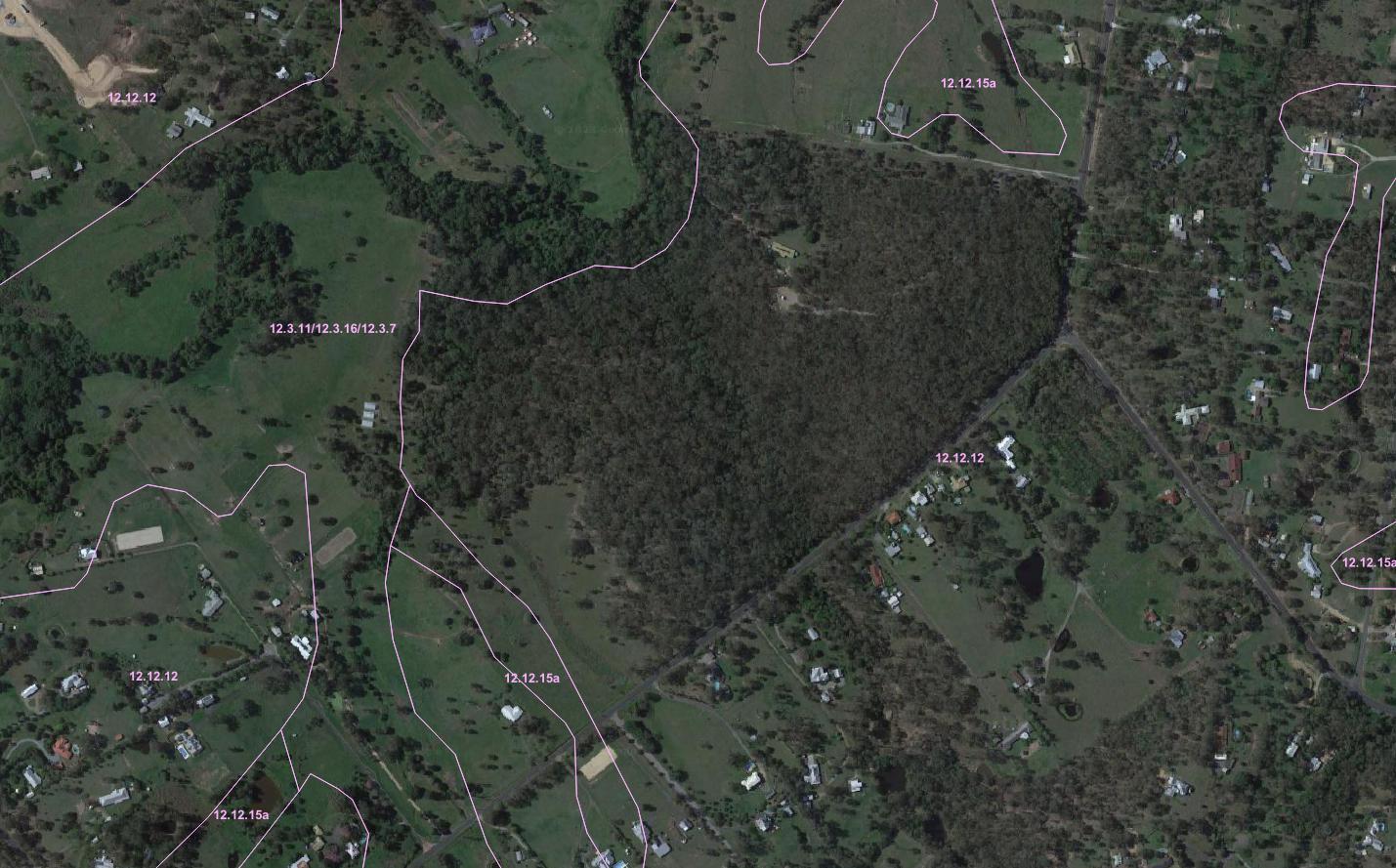

Walk the perimeters of the artwork site and make initial localised observations. Choose and sit down at sites of interest in the ‘passive’ and ‘active’ areas of the artwork, and observe and listen. Observe local plants or plant communities of special interest – which will be temporal in some cases, and sustained in others. (e.g. on 16/4/24 I spotted Scented top grass and Black spear – mid/late summer species doing well in the wet and warmth of this years April – so some sites might flourish at sometimes and be dormant other times of year). Make sketches, think small – begin to consider how to build up deep ‘observations’. Be, and don’t be, methodical. Identify a possible series of representative sites to place future artwork elements – in both the grassland (active) and gulley (passive) areas. To record these activities place custom markers at points of interest.

This action was initially completed on Tue 16 + Thurs 18 April – using star pickets for marking key sites (locations of interest/monitoring camera sites). Future intention to use coloured site markers to in the grass to determine paths/minimise disturbance. (e.g. I sat at places of interest (usually where a new tree was pushing through the grass as a place to start), over time just quietly observing – as a result of this action I experienced maybe my first ever hay fever that night, noticed the profusion of insects most notably arachnids, ragged re-growth, and softness under as the Fimbrystis slowly dries out to late April maturity).

As the late afternoon wore on my quiet, solo process was surprised by an unexpected person moving on the other side of the rise within SERF’s boundary – walking slowly through the grasses as if searching for something. I’d already heard from site manager Marcus Yates of a rare Quail siting in that area – but this chance meeting was pivotal – and threw into doubt how which ways the project might use the site going forward. (see The Quail Turn post)