Advanced Artwork Burn Site Soil Sampling Stages:

After our initial forays into the micro-biology of the soils at the artwork site, Dr. Eleanor Velasquez and I returned to A/Prof Carrie Fisher’s lab to delve further into the investigation of the health of pupureocillium bacteria. This lab investigation marked the culminating stages of A /Prof Hauxwell-led study into the effects of the burning we had done in 2023 – and how it had affected soil bacteria under the burnt areas (the area we were now calling the wet gulley or wetland). This marked the end stages of the 2nd stage of what will now be a long-term study into the effects of burning on particular soil health indicators.

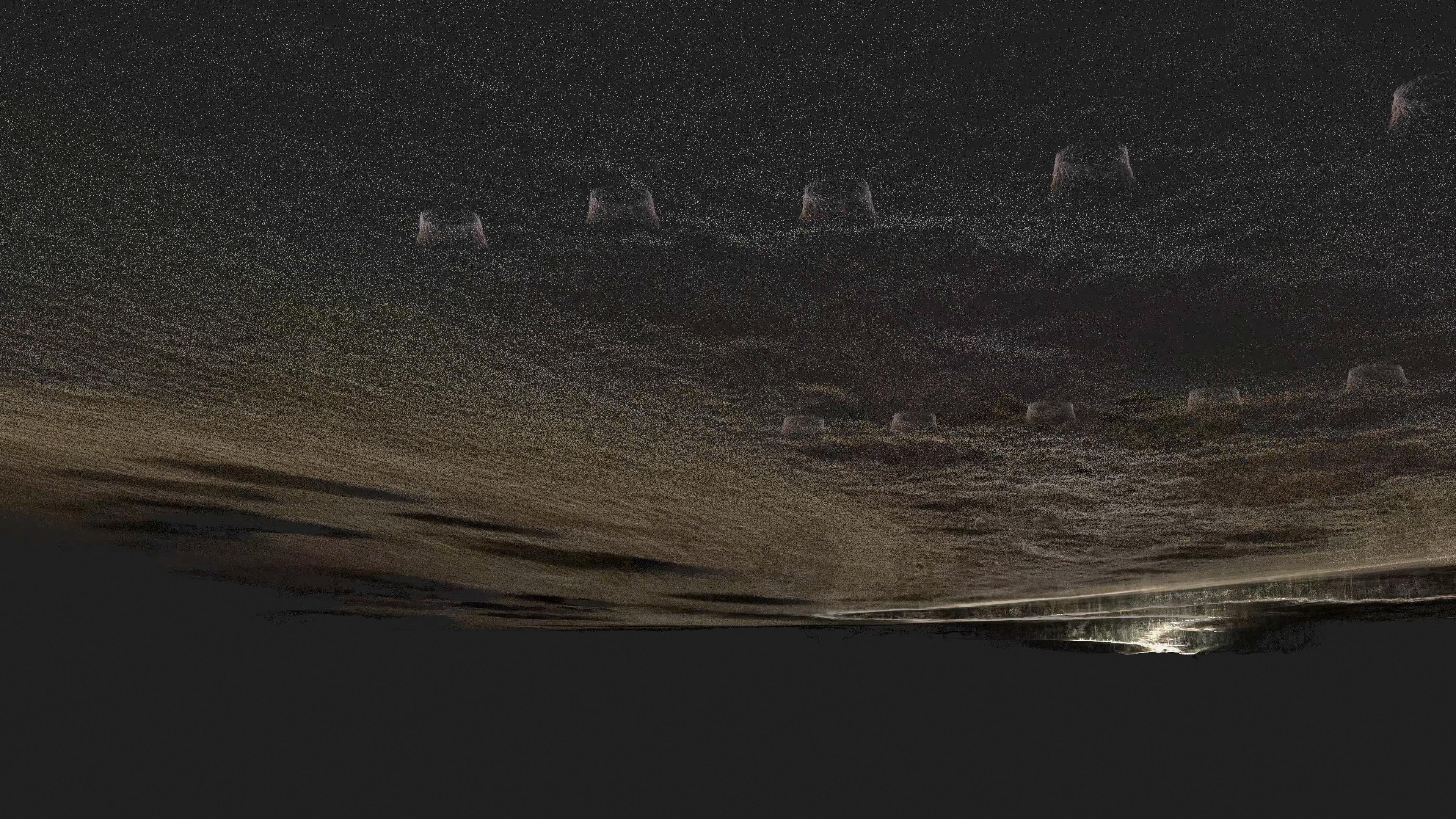

This therefore was time to really begin to understand what bacteria morphotypes had been identified and isolated from the soil samples across the site’s 13 transects (a feature which I also added to the loosely representational animation I was creating for ISEA 2024, as a series of stylised, subsoil ‘pots’ – see screenshot below).

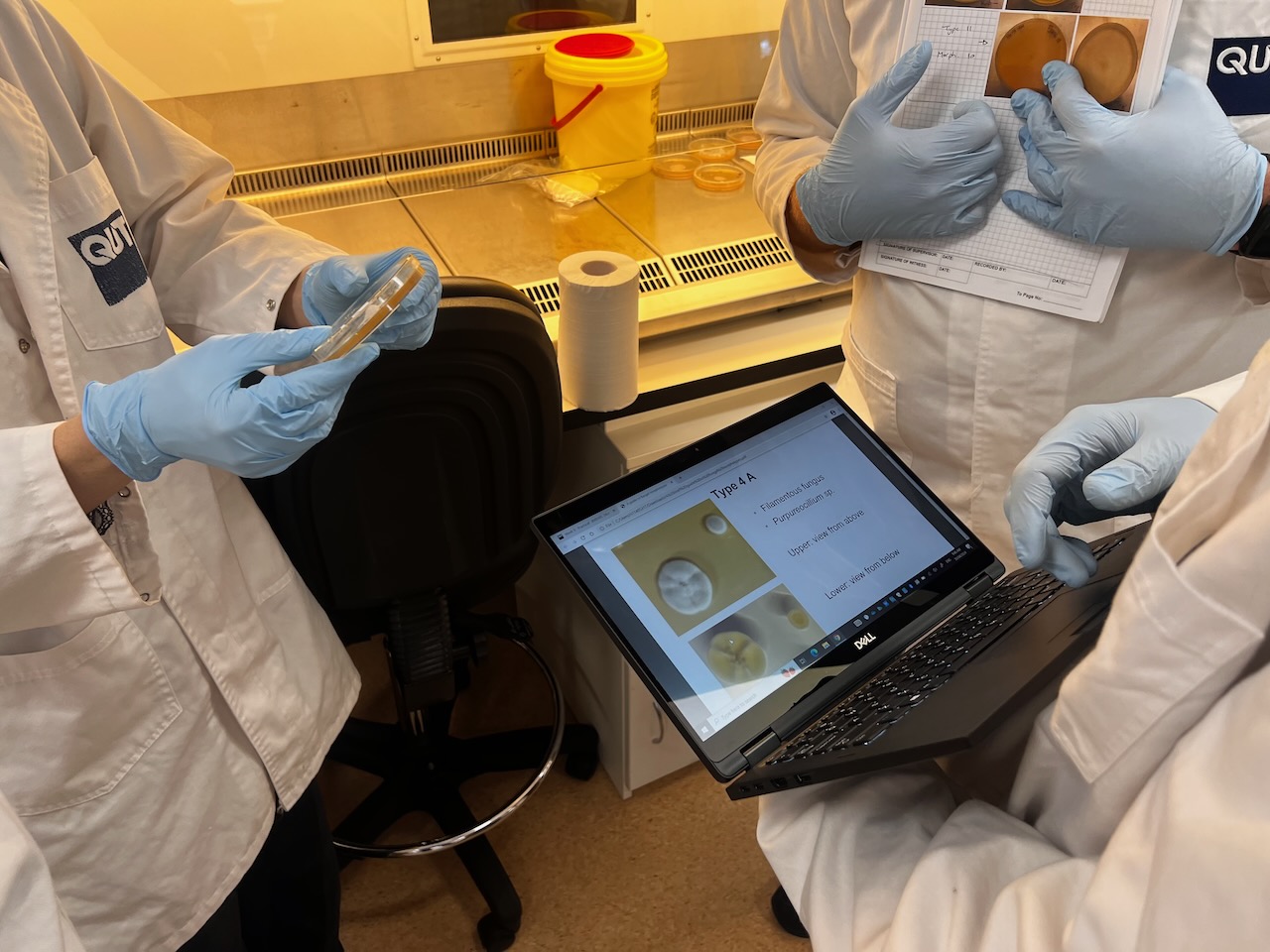

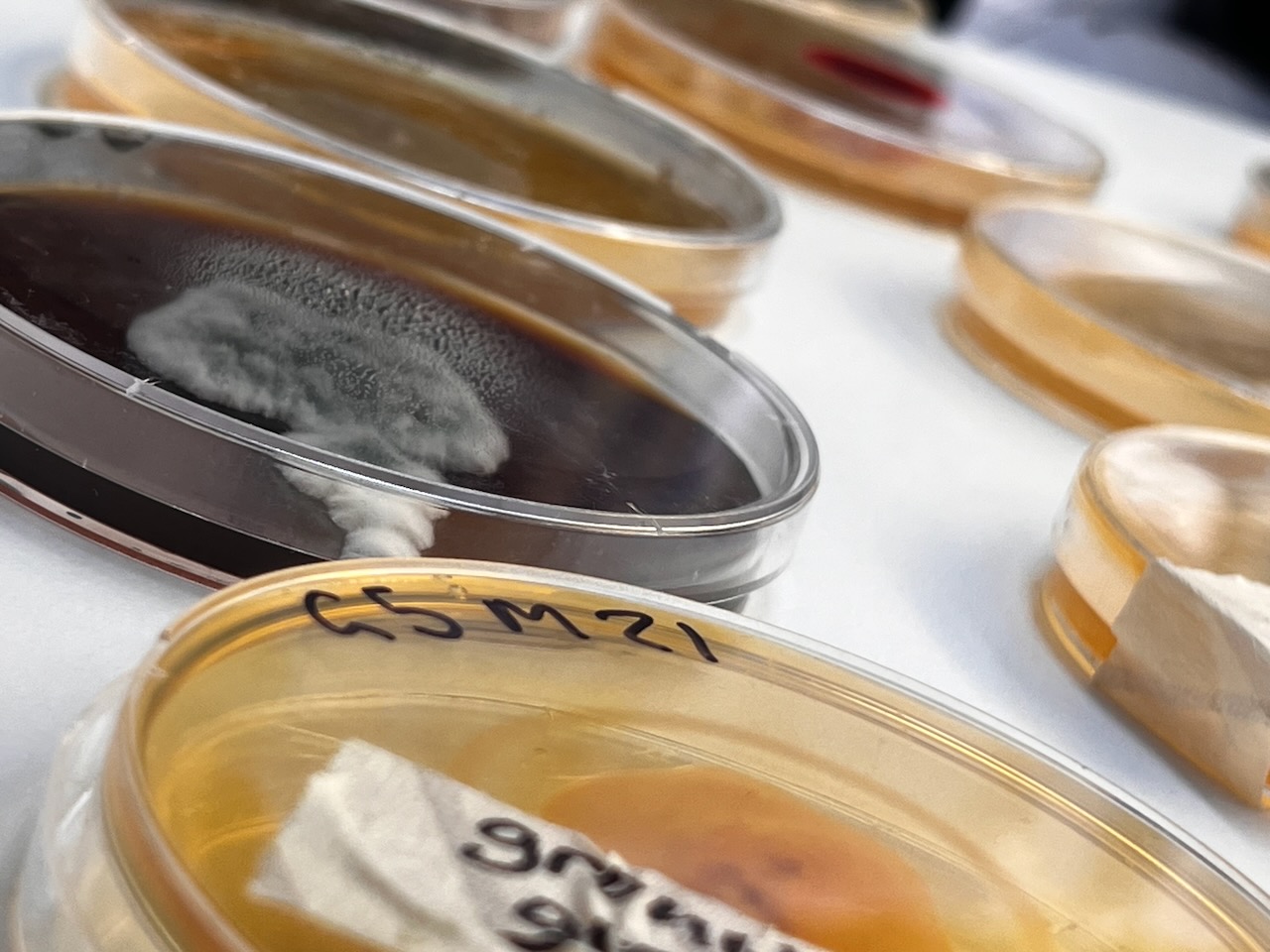

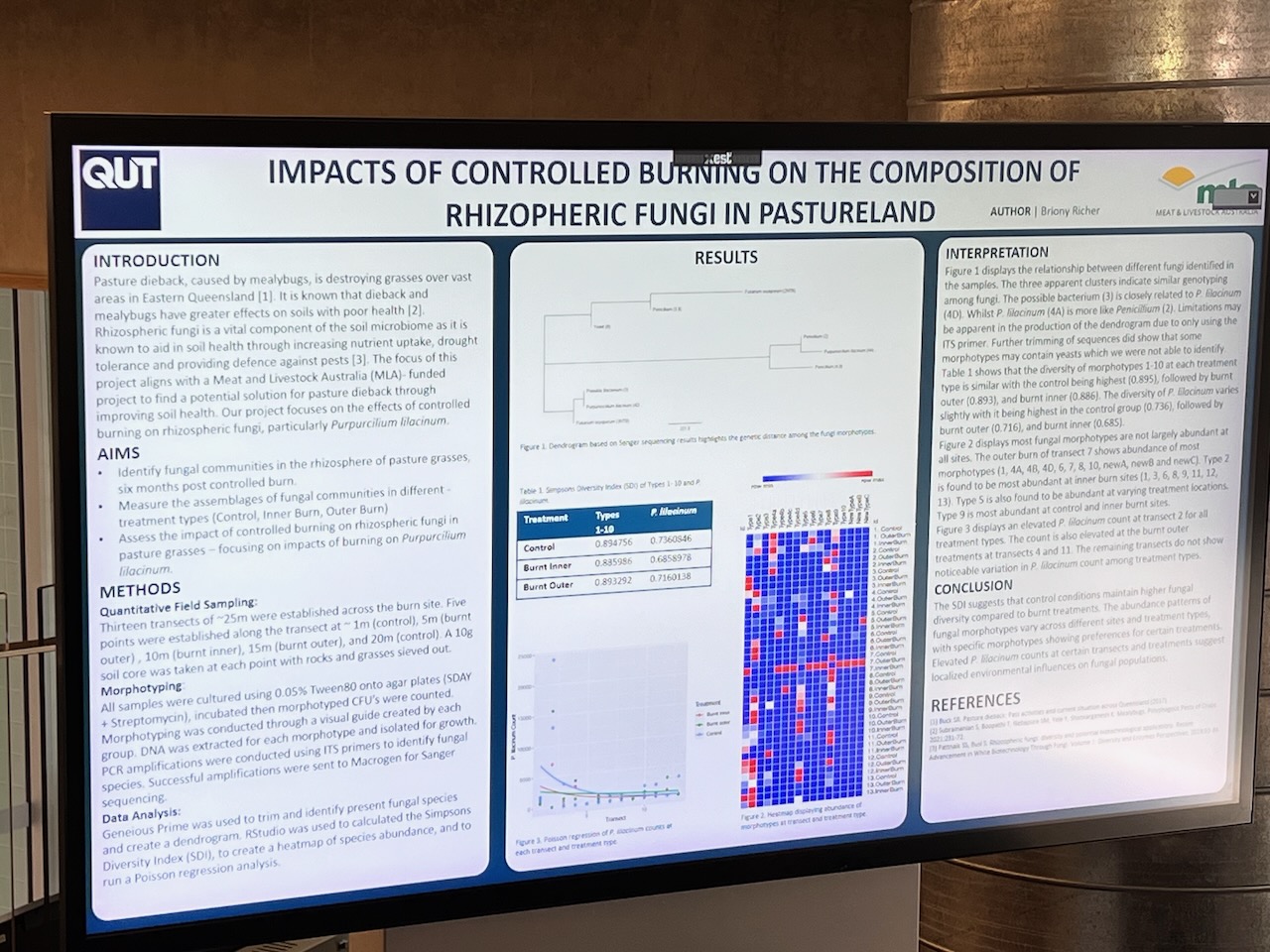

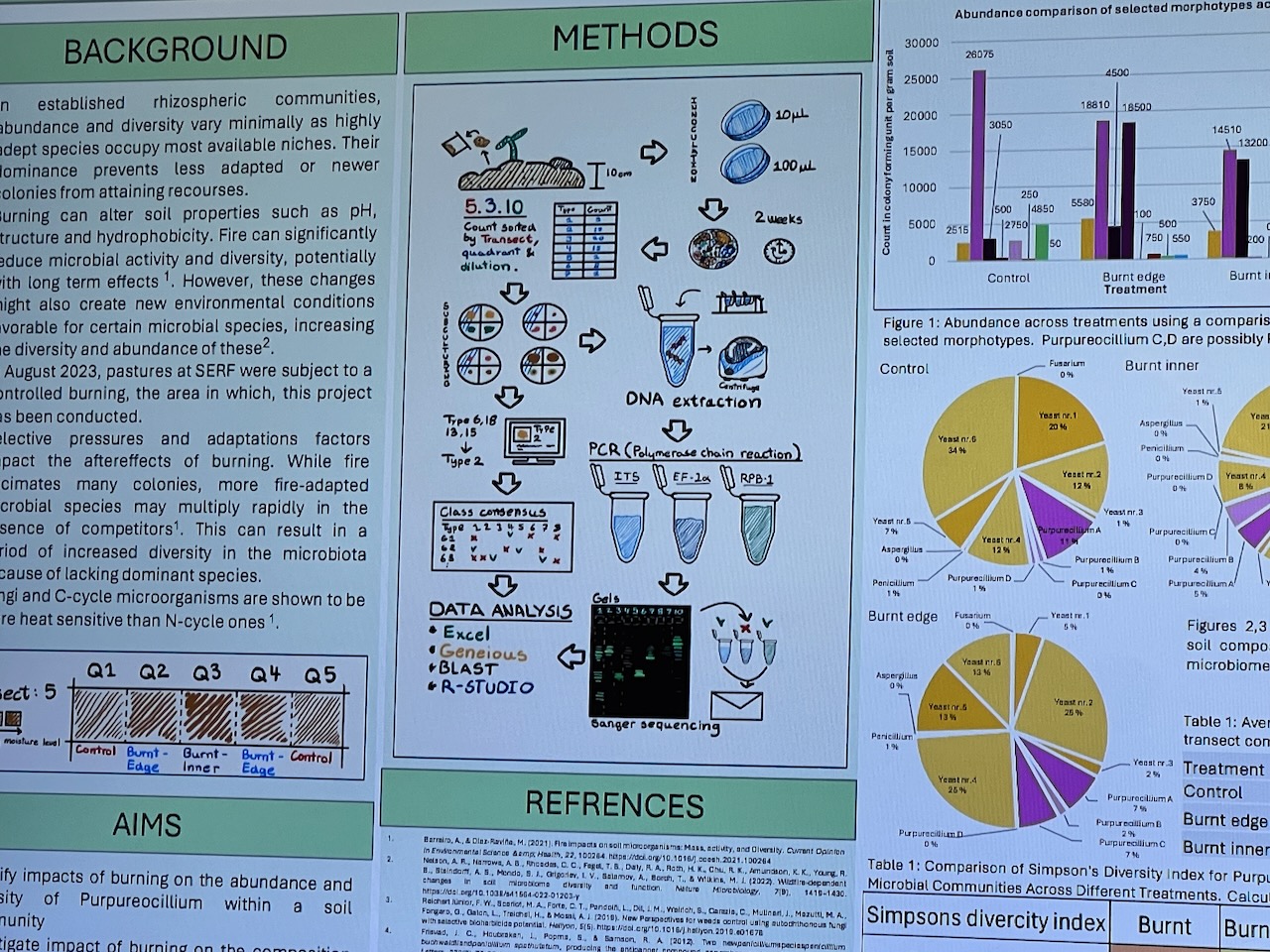

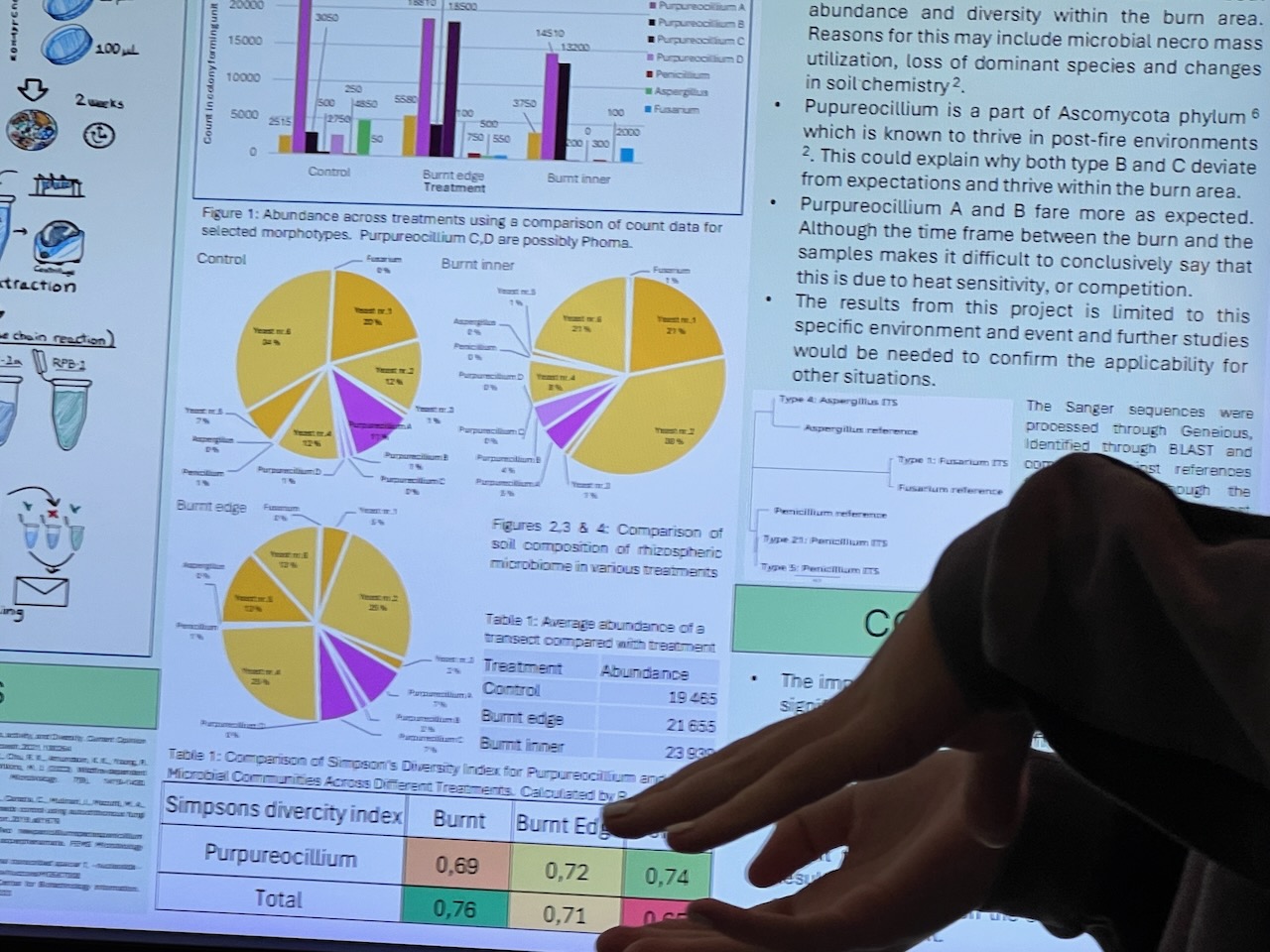

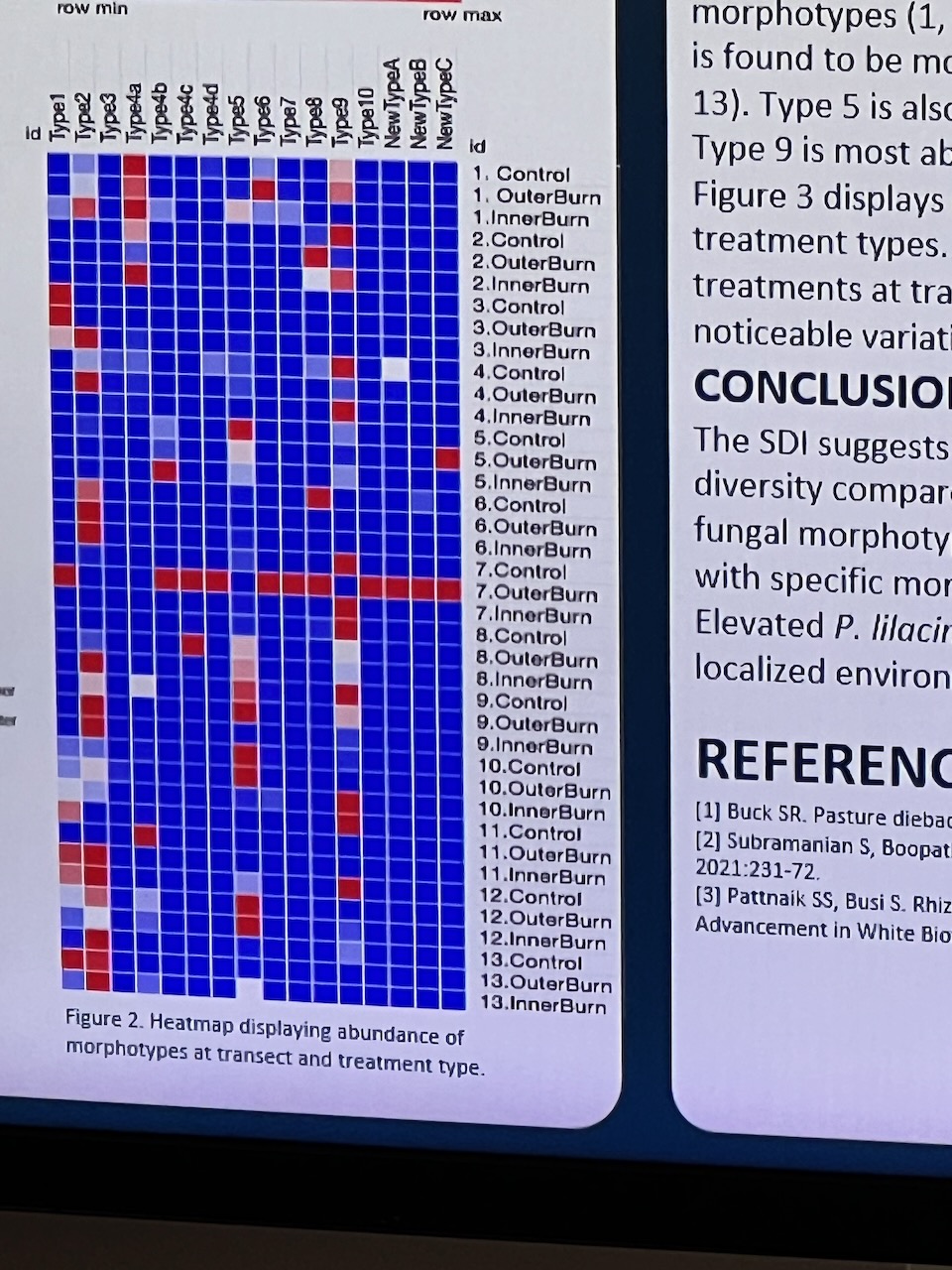

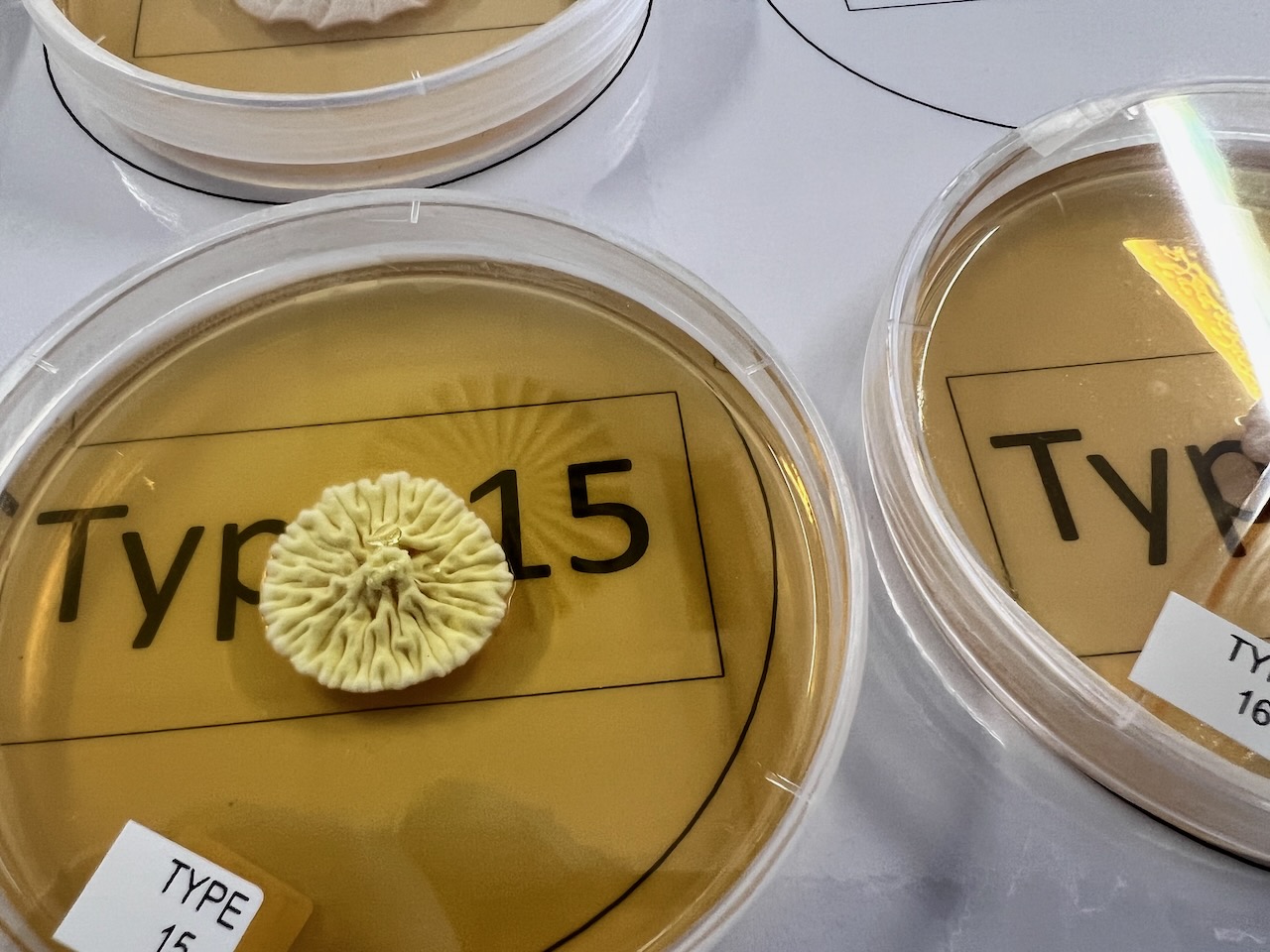

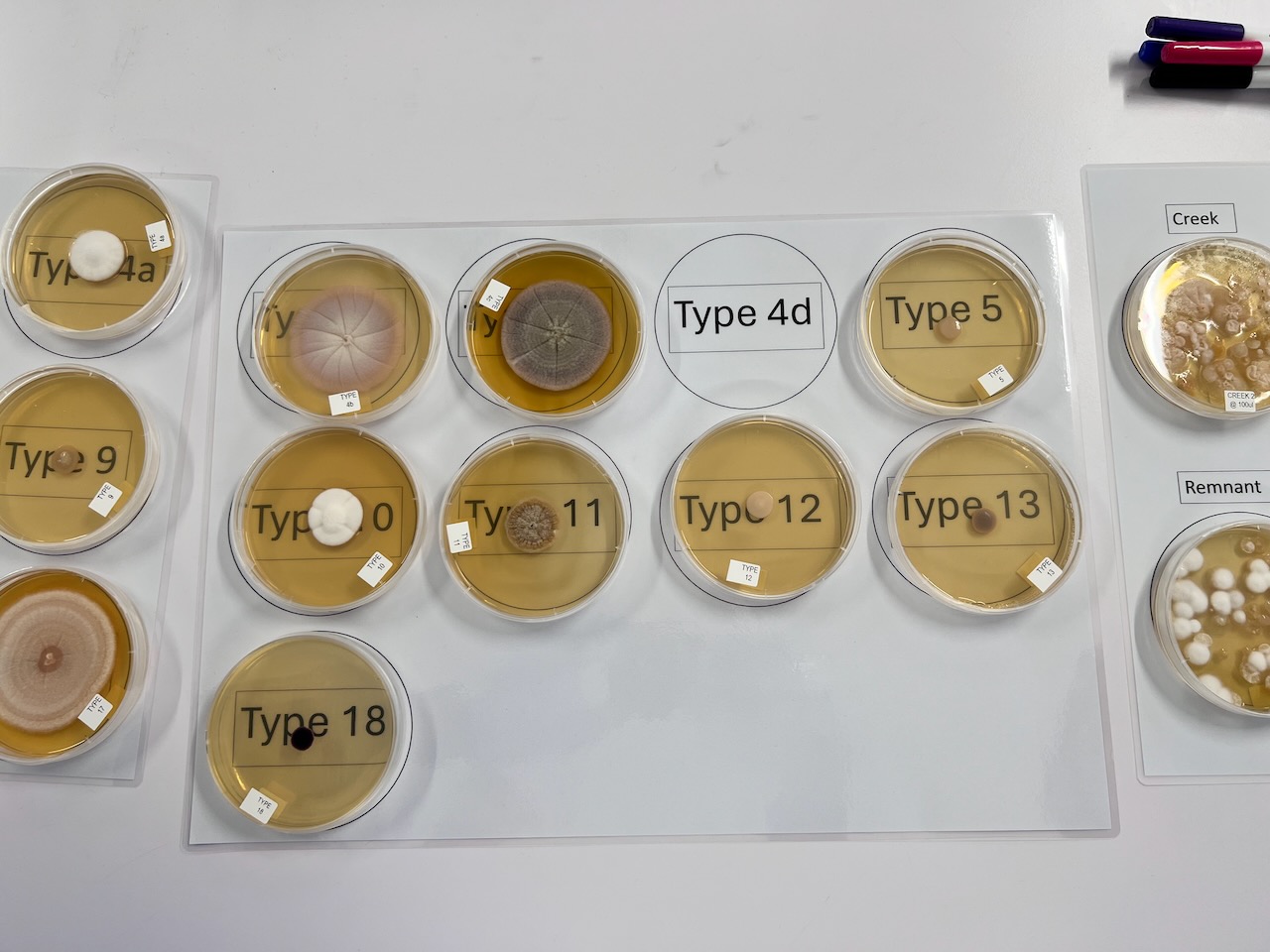

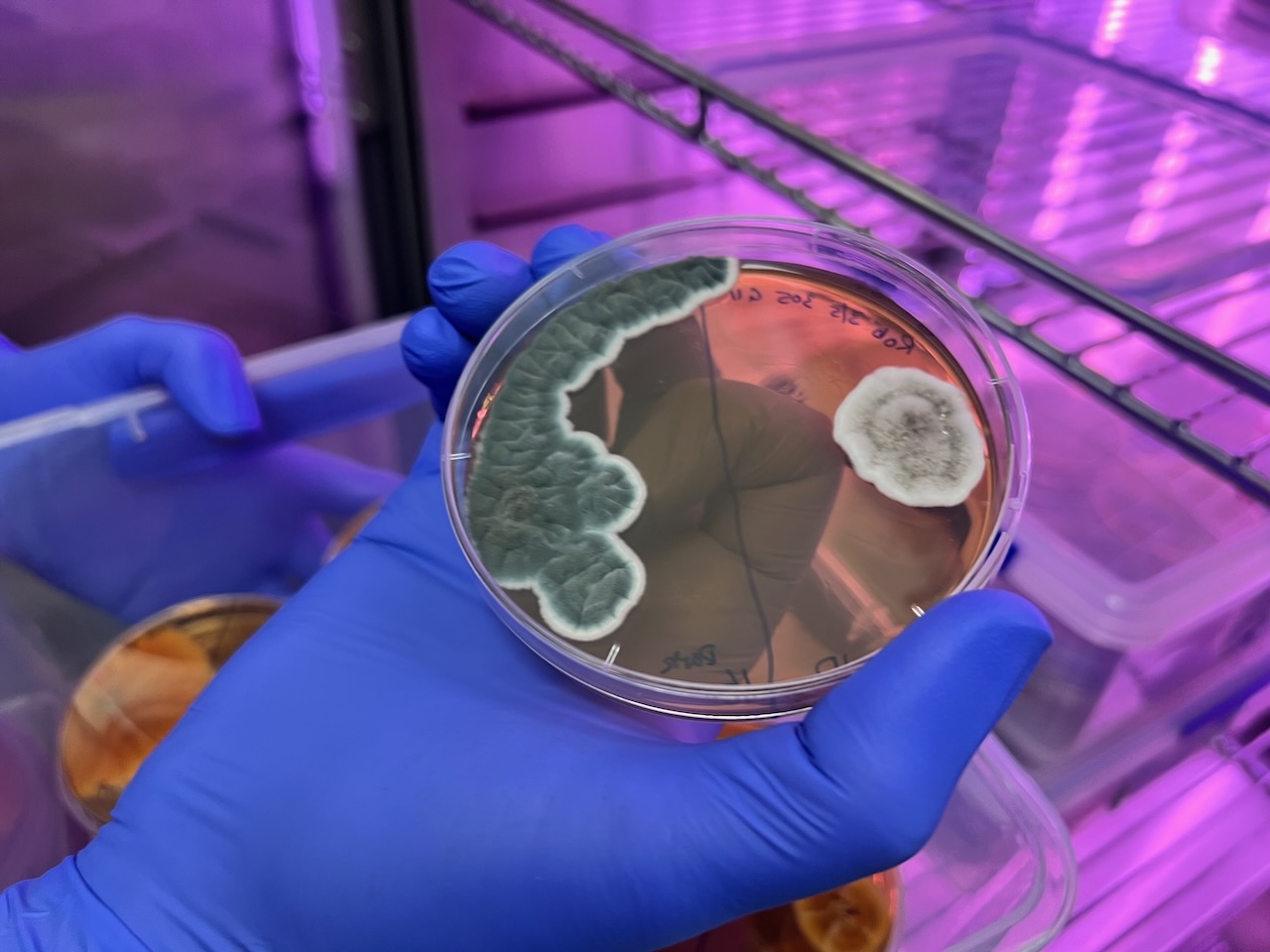

Whilst this visit therefore allowed us to view the outcomes in the flesh, a couple of weeks later we were also able to listen to students present their analysis of the fungal strands that they had being attempting to identify, culture, re-test and analyse from the site – as shown in the following images:

Presenting the Results of the Fungal Analysis

Results of the effects of the burn on the artwork during were subsequently presented at a student poster session to Faculty staff (with Dr. Eleanor Velasquez and myself present as guests). Dense information was presented via digital posters on large screen TVs in order to communicate outcomes – mostly in a language suited to fellow scientists. These presentations predominantly focussed on the differences between samples at the transects – i.e. whether the fungal activity differed significantly deep inside, towards the edge or on the outer of the transects (running across the artwork burnt gulley site).

Given the number of variables – and the time the survey had been done after the burn (several months) – some student results were arguably less clear cut than perhaps we might have expected – but most showed some indications that the fungal diversity had suffered initially towards the centre of the burn site – with the assumption that it would return strongly into the future.

A Further Morphotype Workshop

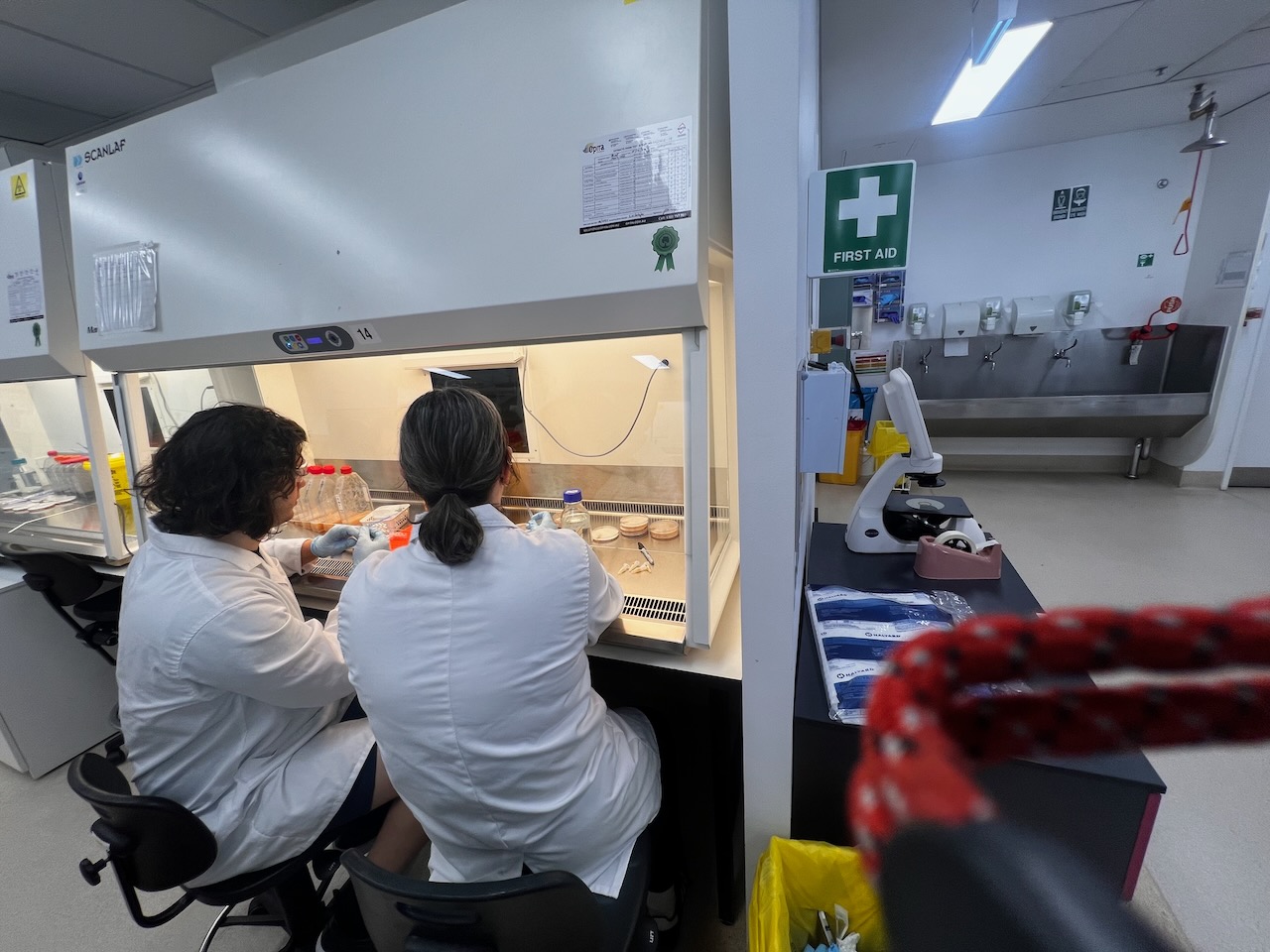

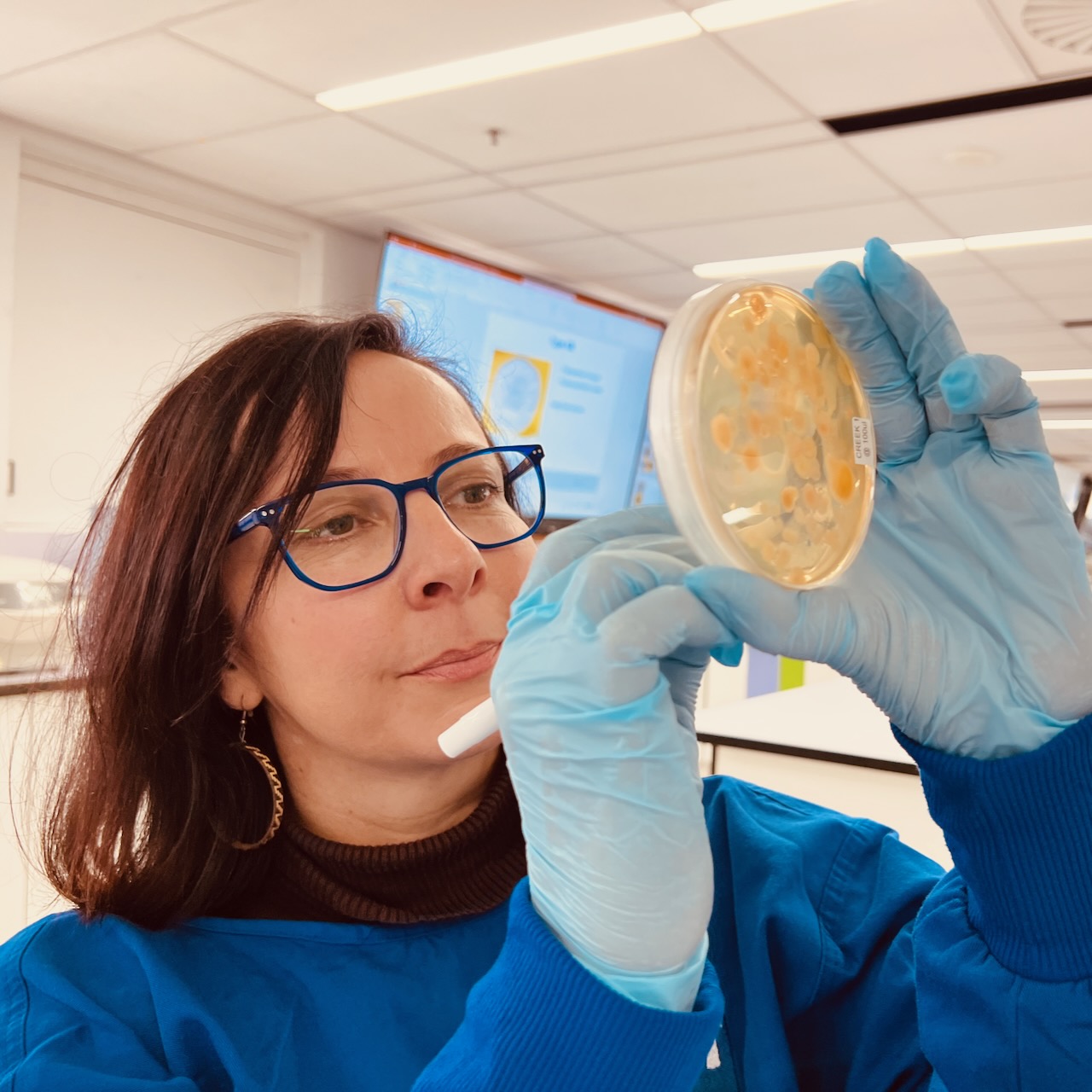

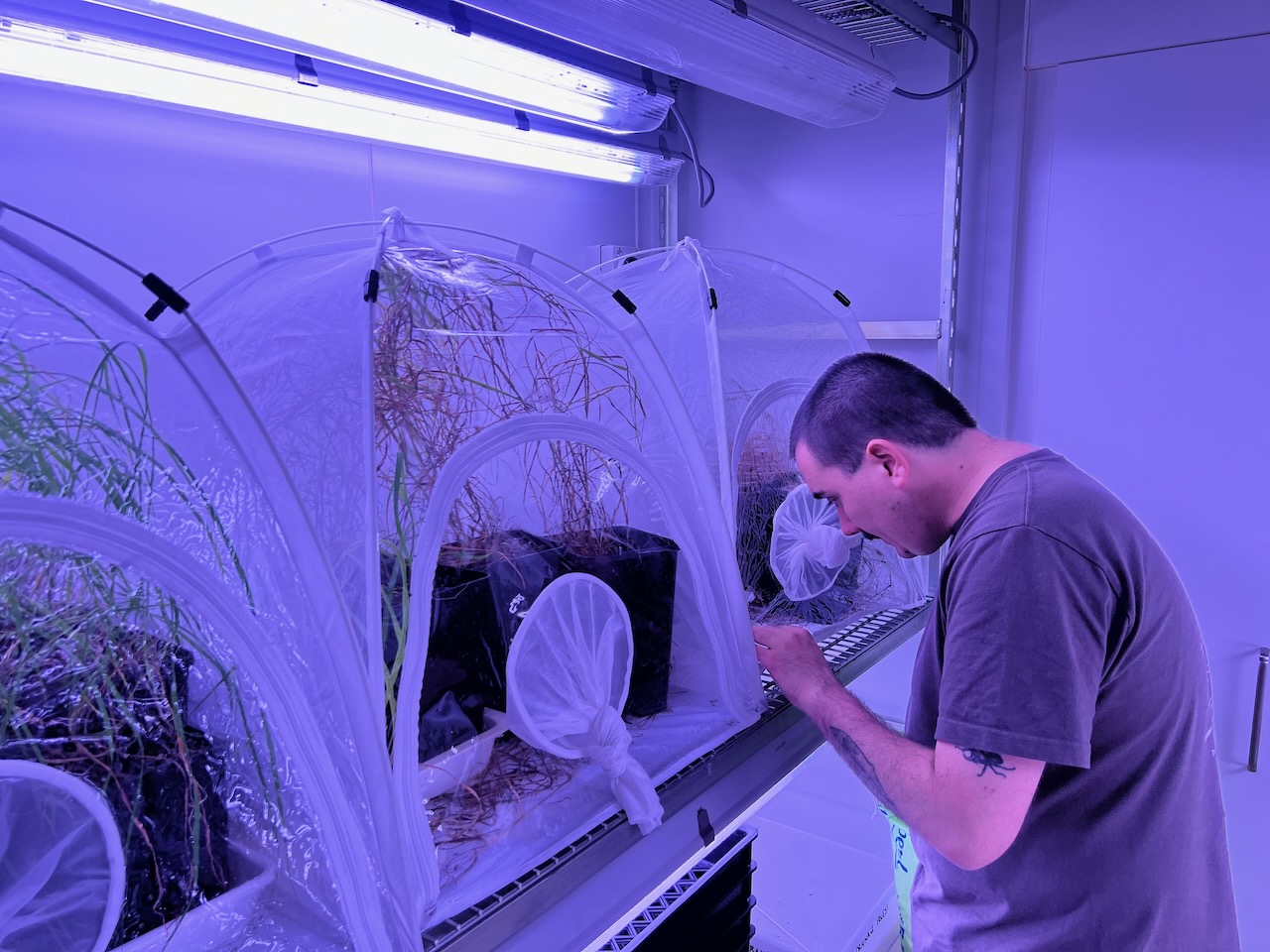

Around that time Eleanor and I were also invited to participate in another ‘microbiology 101’ workshop – which we attended with interest given its hands on possibility and our need to increase our understanding of the processes involved in culturing and analyse. At this lab (led by A/Prof Hauxwell and initiated by Prof Jenn Firn (another prior collaborator from my prior Carbon_Dating project).

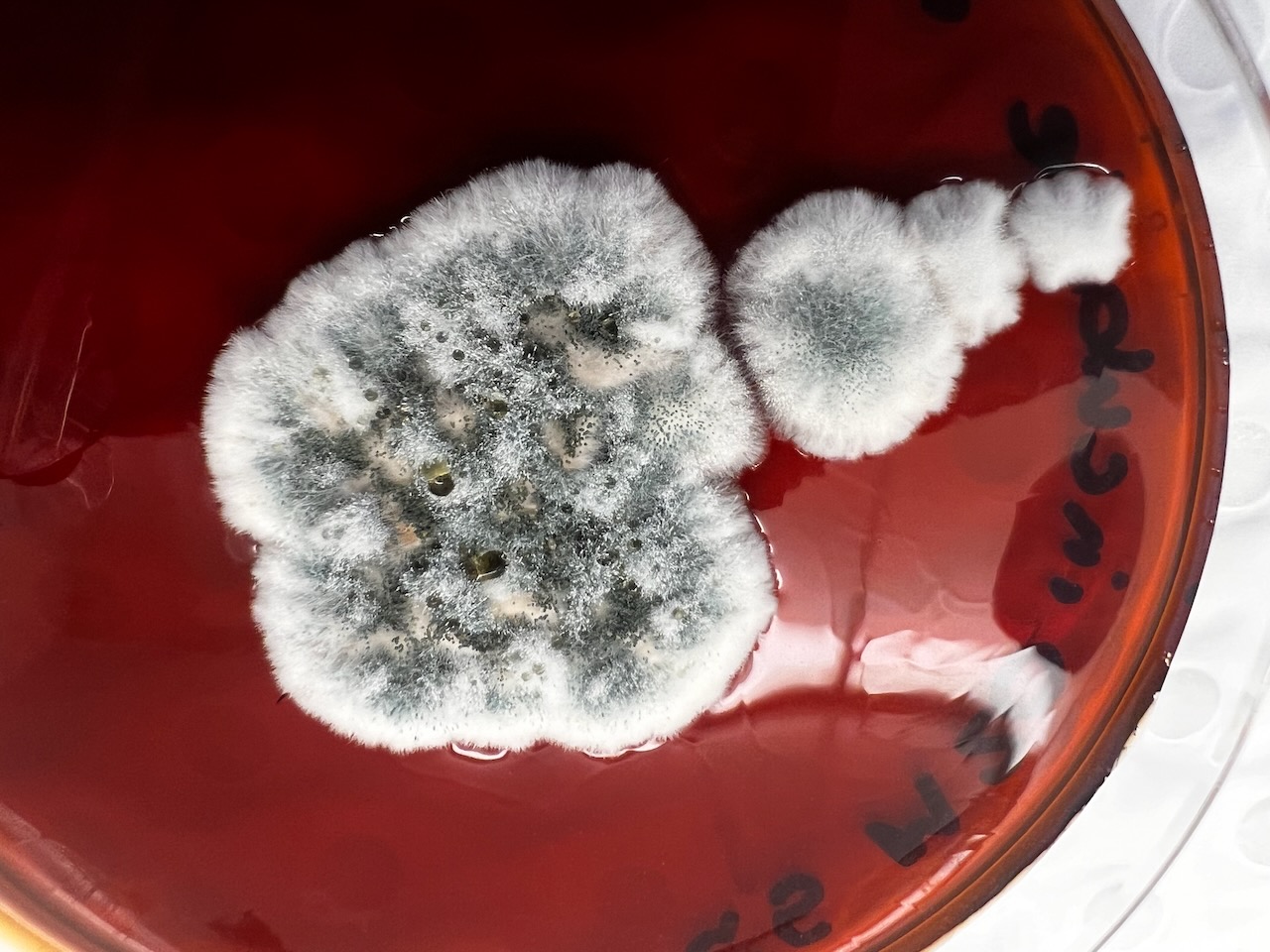

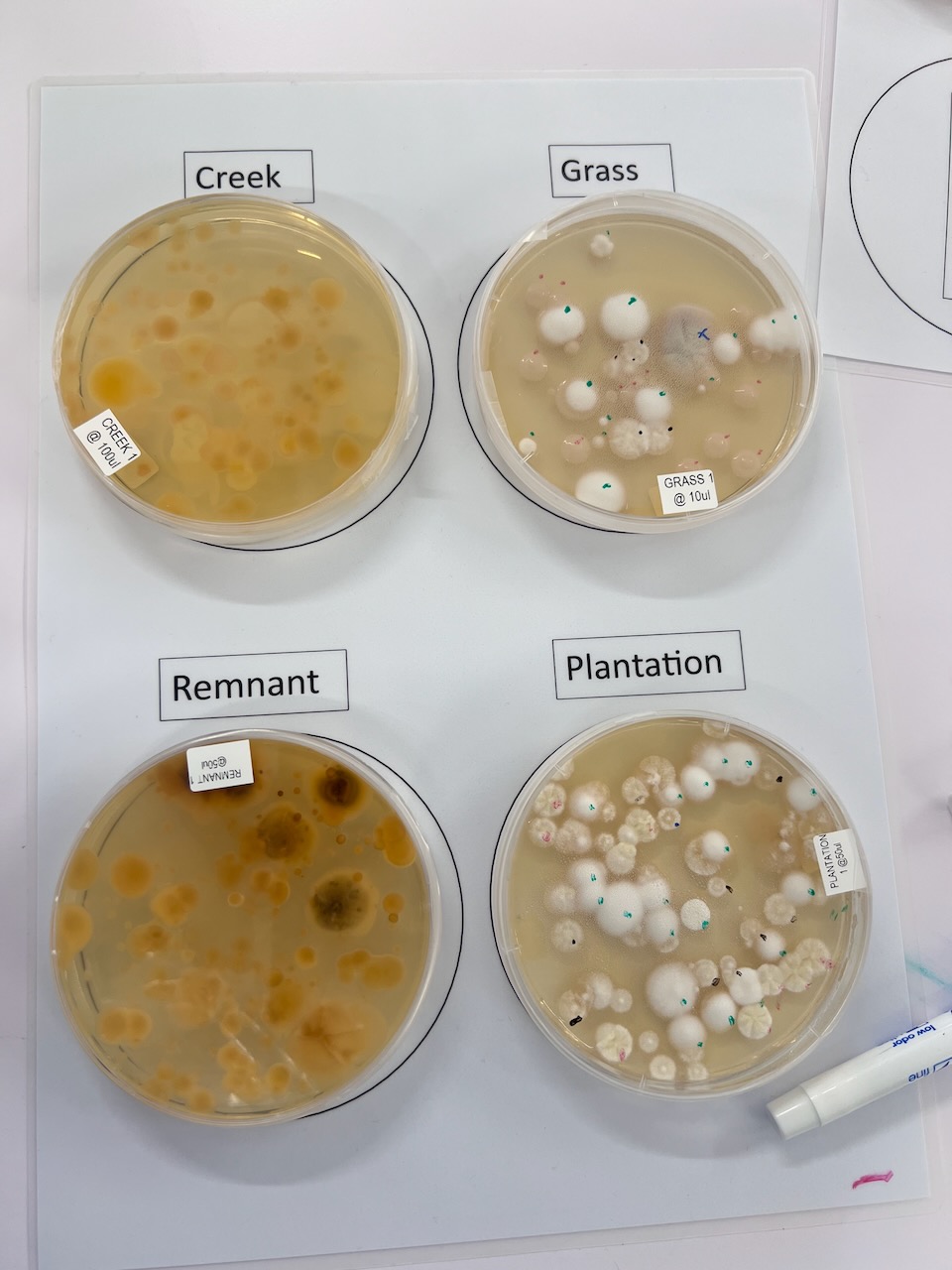

During this session we counted professionally pre-prepared morphotypes (a morphotype refers to the ability of certain fungi to switch between different growth forms) from agar plates with isolates (a specific strain or individual fungal soil organism that has been separated or cultured from its natural environment). This is the sort of class that’s run by the science faculty to first years a taste of biology and ecology.

The session allowed us to investigate a full set of clean, cultured reference specimens from 2 years of sampling at another local site, plus some fresh soil samples plated out for us. We then did some basic quantitative assessment of morphotypes using a guide provided – which would allow then heat mapping (two-dimensional tables of numbers as shades of colours – a popular plotting technique in biology, used to depict multivariate data) and the derivation of a Simpsons diversity index (a measure of diversity which takes into account the number of species present, as well as the relative abundance of each species).

Developing a Timelapse of Fungal Growth

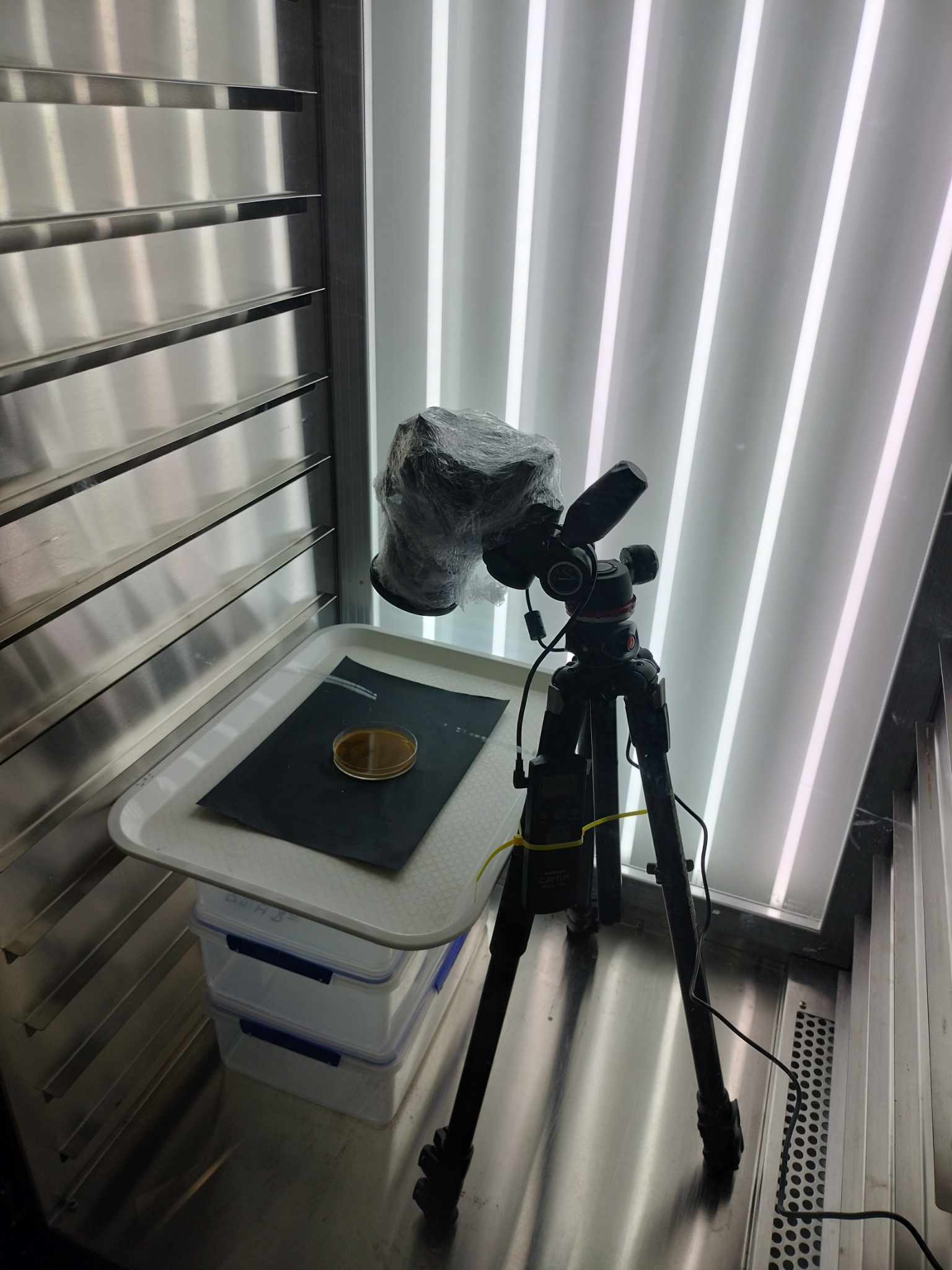

One of A/Prof Masters students Edward Bryans, assisted by Genevieve Dickson very kindly agreed to setup a time-lapse for us so we could see the development of these bacteria across time.

Time lapses are a bit of a staple of science shows, but trying to make your own is a totally different thing as it becomes an ’embodied’ experience. If you watch someone’s else’s – you don’t really know how long it took – but making it yourself, you have the experience of the actual bacteria that you’ve sighted – that can ultimately become compressed into those 30 seconds. You share life with that thing that you’ve been photographing, and by embodying it, it becomes a totally different way of experiencing and understanding the world that more than human is a part of.

Edward and his colleague Genevieve built a simple system in an airflow protected cabinet in their lab using a 35mm camera with protective coverings – so that we could monitor the bacteria in action. The process turned out to be quite a fiddle – with the heat of the lights drying out the fungal plates and restricting growth – so it’s an ongoing project!

This is the first outcome – showing the purpureocillium and a rather more aesthetic contamination yeast moving in unexpectedly! More to come as Edward and Genevieve work out an improved method to get a larger more impressive growth 🙂